We are Tiger Pajamas Web Site Company. Note, if you haven’t already, the splitting of “Web Site” into two words; the usual style is to make “website” a single word. I’ve used this spelling periodically for a while now, mostly because I think it’s funny, and if you ever asked me why (no one ever did), I would have grinned sheepishly and shrugged. But as we start to flesh out what our company is, and what exactly we’re shipping, I’ve been thinking about if it’s definable at all, and if so, what it might tell us about what we’re doing. What, exactly, is a Web Site?

Once upon a time, there was a social media company called Twitter. No idea what happened to it, I’m sure it’s fine, but back in the day I had an account, and one day in December of 2021 I wrote a tweet:

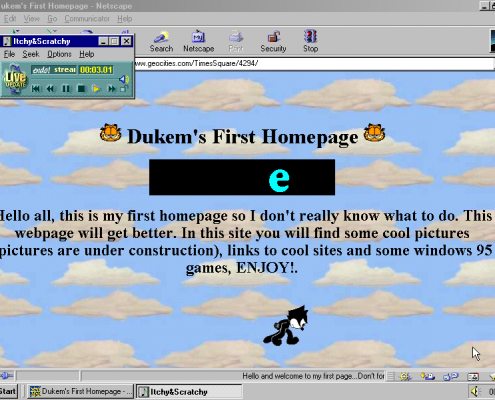

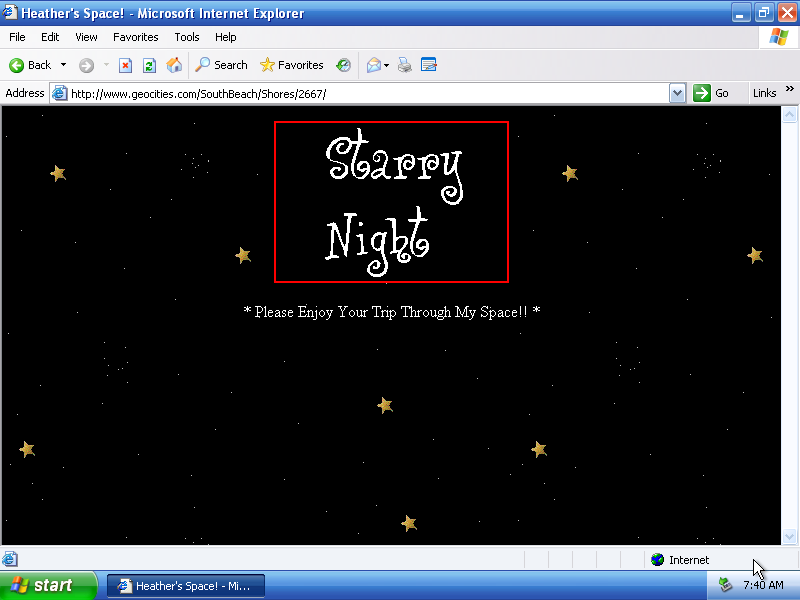

Web1 was a bunch of pages with names like “Dan’s Web Site” made from raw unstyled HTML and it contained a 16x16px gif of a shooting star and 3 paragraphs of bright blue text about Nickelodeon shows and people keep trying to convince me that things have improved since then

This is the first time that I spelled “web site” this way, and it’s clear I was going for a Vibe. Let’s break it down a bit.

Web 3, 2, and 1

The timing here is important. Late 2021 and Early 2022 were the high points of a cryptocurrency bubble, which proponents were calling “Web3.” The idea was that cryptographic wallets would form the next widespread evolution of the internet, following on the heels of “Web 2.0”, and form a new internet paradigm in conjunction with large virtual spaces that you’d visit with virtual reality equipment. The Cryptographic Metaversal Revolution ended up pretty spectacularly Not Happening, despite billions of dollars thrown at the idea, but there was a lot of hype built off of the general feeling that Web 2.0 had run its course and it was time for something else.

I don’t know if there’s a consensus definition, but in my mind Web 2 is roughly synonymous with social media and the smartphone; Facebook and Twitter came along, followed by Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat, LinkedIn, and TikTok, and we all exported our social webs to centralized content feeds that lived in our pockets. This move changed our culture forever, and brought a lot of new things with it: clickbait, influencers, E-Commerce, viral disinformation, #trending, and algorithmic recommendations became daily facts of life on the Internet.

Web 2 brought scale to the web. A few companies captured the vast majority of traffic and could send millions of people to your page. If you could figure out what the recommendation algorithm wanted, you could make being online your job, through advertising revenue or merch sales. The stakes were high, and lots of people and companies began shaping their content, conciously and unconsciously, with an eye for appeasing the mechanical recommendation engines that sifted through the petabytes of user-generated content that was constantly being uploaded. This is also where Search Engine Optimization, the dark art of gaming Google’s search algorithm to boost your page to the top of their results, began.

Web 2’s legacy is, in part, an Internet of sludge, with generative AI picking up where human content farms left off to flood search results and social channels with low-effort content marketing at a scale no human can match, all to chase rapidly declining ad revenue.

The real fun question, then, is “what was it like before?” Younger internet users, who arrived on the scene after this phenomenal consolidation had already occurred, get only whispered myths of that primordial time. This is where Dan, the Web Site maker I imagined in my post, would have done his work.

The Wild Web

Ultimately, I wanted to express that things were better in a lot of ways in “Web 1.” You needed access to a server, and probably had to teach yourself the networking and coding required to write and deploy your HTML and PHP (if ya nasty), but then you were on the Web, accessible to anyone who typed in your URL. Search was in its infancy (Yahoo was basically a human-curated list of links in its early days), so the way people found your site was different: maybe you’d email your friends the link, or write it down for someone on a napkin. Maybe your friends would have their own sites and link to pages they liked, like yours. But your site would be out there, instantly accessible to anyone who cared to visit it, and there were far fewer best practices about what a site should look like.

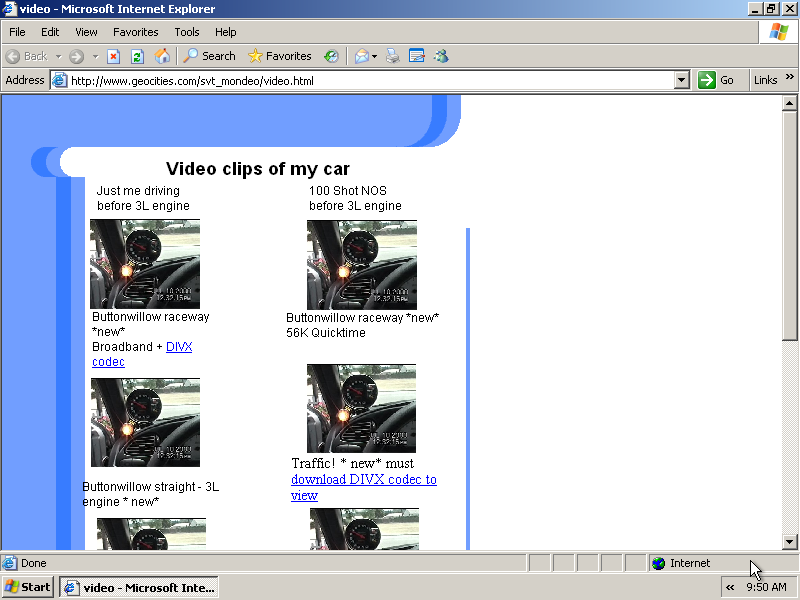

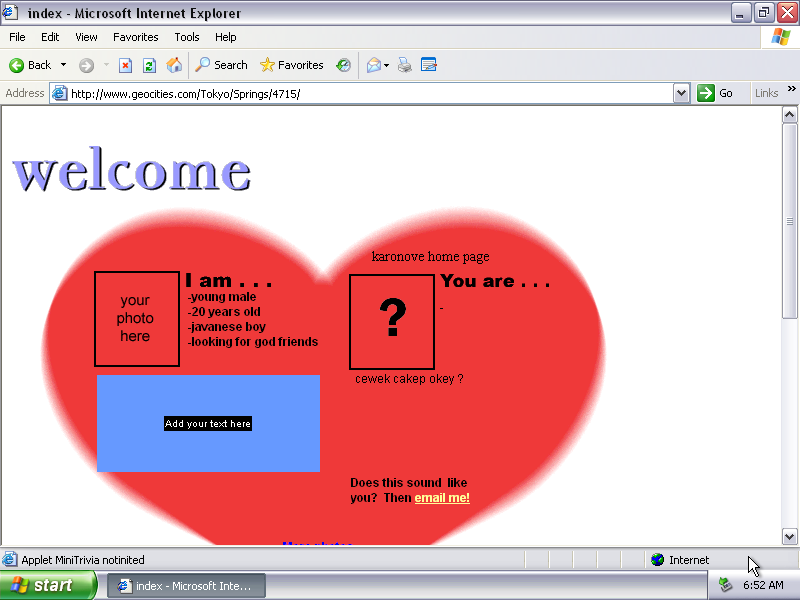

Colors and fonts were styles that were available early, and relatively easy to grasp, so sites of this time were wild laboratories in design. I picture Dan’s Web Site as having bright blue (#0000ff) text on a white background, maybe center aligned because why not, with a couple of left-aligned jpegs thrown in for good measure. There are sites with rotating gemstone gifs and sites that have text that blinks on and off at an alarming rate and there are sites with visitor counters at the bottom. These early sites can look garish and primitive now; we’ve come to expect a certain look and feel from our internet content, and a page with clashing neon colors and a site heading that says “WELCOME TO RAMONA’S NET ZONE” in red bold italic underlined Times New Roman might feel amateurish. But those standards of good design didn’t exist yet! We were making them!

Our sweet, dorky Dan is writing about TV shows he likes because he doesn’t have Twitter, or Letterboxed, or group text chats with his friends. He has something to say about the Angry Beavers, and his little corner of the Internet is his place to say it. Once again, without a decade of conditioning about what parts of your digital life go where, it can be anything. I used to see rock collections and conspiracy theories and blurry pictures of funny road signs. I once followed a flamewar between rival Pittsburgh-area Thelemite churches, airing their dirty laundry against each other in real time on their homepages.

What’s hard to imagine is that there was zero financial incentive back then. There was no way that your 7 <p>s about Spongebob would go viral (not a thing) and that you’d get a cut of ad revenue (not a thing) or a sponsored content deal with a brand (not a thing). It was all for the love of the game. Once you created your boilerplate HTML page, it turned into a blank piece of digital paper, begging you to reveal what it is you want to say to the world.

The throughline here is a childlike curiosity, an exploration of a new medium with unselfconscious experiments in form and function. Learning by doing, for whoever cared to look. Finding your fellow explorers online and linking to them, learning all the different ways to decorate your digital spaces together. Going to the “computer room” and logging in and typing the URL into the browser bar by hand and checking on your e-buddies. Doing whatever you want because there’s no “right way” yet.

Ultimately, Dan called it his “Web Site” because no one had decided that “website” was a more correct spelling yet.

The Big Orange Splot

One of my favorite books as a kid was The Big Orange Splot by Daniel Pinkwater. In a neighborhood with a strict HOA, a bird dumps orange paint on a guy’s roof and he is inspired to paint the rest of the house, and install palm trees in the front yard, and chill in a hammock all day. One by one, his neighbors attempt to talk him out of it, and instead decide they want to build their dream houses too, after hearing his explanation:

My house is me and I am it. My house is where I like to be and it looks like all my dreams.

The street ends up with houses that look like hot air balloons, gothic castles, and all other manner of things, instead of a the boring row of brick houses it began as.

When I think about what a “Web Site” is in today’s internet, this is what I imagine. A digital space that is fully suffused with the enthusiasm and quirks and humanity of its owner. A destination that is an absolute delight to spend time in and explore. Somewhere that doesn’t feel like it’s constrained in its wanton creativity by arbitrary rules for robots. The beautiful thing is, anyone can have a web site. You don’t have to be an expert! We’ve come a long way since the early days of the Web and the tools have only gotten better. All it takes is some time, an adventurous heart, and something you want to show to the world.

In the spirit of the early web, I made a web site that makes me feel at home on the internet. Check it out at phils-web-site.net.

And if you’d like some help, that’s what we came together to do. Say hello and tell us what your dreams look like.

All web site images courtesy of the excellent folks at the Geocities Institute.